Monthly Archives: July 2014

Tree Facts

Colombia’s Banana Massacre

The ill-trained soldiers stood at the ready by their machine guns. They looked down from their posts on top of the low buildings at the crowd of striking banana workers and their wives and children in the main square. Soon the crowd was ordered to disperse. Five minutes passed. Gen. Carlos Cortés Vargas gave the order to open fire. The machine guns did their deadly work as the crowd surged back and forth, hemmed in by soldiers who had blocked any egress from the killing field. When the smoke cleared, the dead and dying lay where they had been gunned down.

The events of Dec. 6, 1928 in Ciénaga, Colombia, would inspire a famous novelist, topple a government and change the dynamics between a massive corporation and one of the many countries in which it operated.

The massacre was a key part of Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s 1967 masterwork “One Hundred Years of Solitude.” The monumentally lauded writer said he was inspired by the stories his grandmother told him about living in the Magdalena region of Colombia on the country’s northern coast, known as the banana zone for its main agricultural product. At the time he wrote the novel there was little interest and no serious historical studies on the banana workers’ strike that began in November 1928 and culminated in the massacre the next month and subsequent crackdown by the government.

Marquez, who was born the year of the massacre, said he wanted to “write about it before the historians come,” but admitted his version differs from the historical facts, especially in regard to the number of victims. In an interview in 1990 the author said he used the figure of 3,000 dead because it fit with the grand scope of his novel. In reality, it’s been estimated that between 47 and 2,000 people died that day. The extensive range in the death toll is due to the differing figures given at the time between the many factions who had something to gain by either inflating or deflating the numbers.

In November 1928, grumbling among the more than 25,000 workers on the banana plantations of the United Fruit Company turned into a united effort with a well-organized strike against the massive American corporation.

The workers’ demands from United Fruit were far from unreasonable. They wanted a direct contract with the company, six-day work weeks, eight-hour days, medical care and the elimination of scripts, only good at company stores, that were paid to the workers instead of cash. Ten years earlier, the company’s workers had gone on strike with similar demands, but had failed to achieve their goals.

United Fruit was a Boston-based company that had its origins in 1870 when Captain Lorenzo Dow Baker, a Wellfleet, Mass., businessman purchased a cargo of bananas in Jamaica and introduced them to New Englanders upon his return with the help of his partner Andrew W. Preston. Soon people couldn’t get enough of the fruit. Through mergers and acquisitions the company became United Fruit in 1899 and would eventually have its hand in the production and distribution of bananas in a number of countries, including Jamaica, Honduras, Costa Rica, Panama, Guatemala, The Canary Islands, and Colombia.

The term “banana republic” stems from the sometimes interventionist policies of the company in regard to the many countries where they did business, especially in Central and South America. One of the most blatant of these interventions happened in 1917 when United Fruit and its rival, Cuyamel Fruit of New Orleans, pitted Honduras and Guatemala against one another over disputed territory that the two companies also happened to be wrangling over.

While war never broke out, there was blatant manipulation of the nations’ leaders that highlighted just how much weight these American companies had in the countries where they did business. Both companies would also have their hand in the overthrow of each of these countries’ freely elected governments in order to secure better trade deals.

By 1928, United Fruit owned more than 220,000 acres of prime Columbian farm land, with much of it not under cultivation, and held a lot of pull with the central government. When the strike broke out the government sent about 700 troops to quell it. There is still a question on how much, if any, influence United Fruit had on the decision to send in troops. A series of cables from American diplomats to the U.S. State Department shows they were in close contact with United Fruit representatives at the time and that there were discussions of sending American warships to the area because the nature of the strike was changing into one with “subversive tendencies.” An American ship was sent to the area, but the U.S. ambassador said it was non-military.

Government officials in Bogotá were frightened by the possibility the strike was the start of a full-fledged revolution and the possibility of American intervention. This was likely drummed into General Cortes Vargas’ head.

Leading up to the massacre there had been several incidents that had helped the federal government and the general persist in their view that they were facing a much bigger problem than just some banana workers trying to get a better conditions, but were instead facing a “Bolshevik threat.”

There were reports of sabotage against the railway resulting in the arrest of 400 strikers. Much to the chagrin of the military, many of the strikers were released by local civilian authorities. The strikers’ acts against the railway were in response to the military banning the striking workers from using the trains. According to some sources, the strike was building into a larger movement, gaining support from local planters, townspeople and the press. It also included the involvement of the leftist political party, Partido Socialista Revolucionario.

Meanwhile, the government conferred state of siege powers to the general and the next morning he and 300 soldiers faced the 1,400 or so strikers and their families in the town square who waved Colombian flags and shouted slogans. At 1:30 a.m., Dec. 6, 1928, as soldiers looked down from their machine gun nests along the building surrounding the square, the crowd nervously milled about. The sound of drum beats were heard followed by the voice of one of the officers ordering the crowd to disperse. Five minutes later there were three short bugle blasts and the guns began blazing. The initial reports said eight people had been killed and 20 wounded, but the figures kept going up with some reports giving the figure as more than 1,000 killed.

This was the start of a time of repressive measures in the banana zone, including arrests of the strike’s leadership and martial law within the region, including travel restrictions for its citizens, that lasted nearly a year.

Jorge Eliécer Gaitán, a congressman with the Liberal Party, rose to popularity when he railed against the government’s killing of the strikers and their families. He toured the banana zone and gave speeches in person and on the radio painting the Conservatives as puppets of American business. During a speech in Colombia’s lower house of Congress he held the skull of a child who had been killed by the Army.

Twenty years later he would be assassinated, an act that ushered in a period of violence in the country known as La Violencia.

Cortés Vargas, who was demoted after the massacre, would only admit to a death toll of 47 civilians. He justified his actions by saying if he hadn’t acted there was a real possibility of American intervention to protect U.S. citizens and property, among other reasons.

In the aftermath of the massacre the Conservative government was swept out of power in the 1930 election with the Liberal Party rising to the fore for nearly 20 years. The new government tended to support the unions, leading to changes in the banana growing industry in Colombia. Another important result was the inspiration it provided Marquez who salvaged a mostly forgotten moment in Columbia’s history and created one of the world’s great pieces of literature in the process.

Great Bargains

In order to secure a three-year purchasing contract with the state of New York, office supplier Staples agreed to sell 291 common items for a penny. They hoped to make up the difference in sales of higher-priced items, but the company neglected to put any limits on the penny purchases. You can imagine what happened. Schools, prisons, charities, and other agencies ordered “staples” such as tissue, paper towels, tape, and batteries by the truckload.

The Monroe-Woodbury school district, about 50 miles north of Manhattan, was the top bargain hunter, taking delivery of $677,000 of penny items at list prices during the contract’s first few months, paying $299.15. The numbers come from spreadsheets provided by the state in response to a Freedom of Information Law request.

Sheri Patterson, finance officer at Monroe Woodbury High School, said boxes were “stacked in hallways…we didn’t have any place to keep” them.

There were surprises. Ms. Patterson thought a penny paid for a roll of paper towels—instead, it was for a 24-roll pack. The school received 53 packs, records show. “We were just wondering whose idea this was,” said Ms. Patterson, “and if they still had their job.”

Staples declined to comment on personnel matters.

Many of the penny items ordered have not been delivered, and the state is negotiating with Staples to fulfill the terms of the contract.

A coveted penny item was a 64GB SanDisk flash drive, a large “thumb drive” to store or transfer data. It listed for $249.99 but recently was priced at $54.99 on Staples.com.

Customers ordered 128,978 of them in the contract’s first few months, documents show, compared with anticipated annual demand for 33. Staples delivered 1,080 in that period. Had it delivered all those ordered, it would have sold drives with a current retail value of $7.1 million for $1,290.

Whoever made the estimates of how many items would be purchased forgot one basic rule of retail: people will do without expensive items, but will buy if the price is right. Staples’ estimate of their loss has to be taken with a grain of salt, however. Who pays $2 for a single pad of Post-it notes? Or a thousand dollars for a shredder? I have a shredder and a bag of Post-it notes for an investment of about $6, although they’re not the same brands.

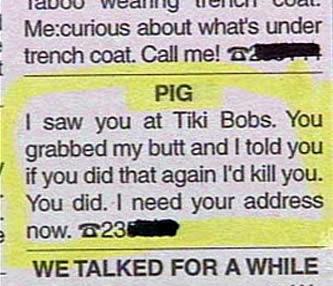

Funny Classified Ads

The Sawney Beane Case of Cannibalism In Scotland

Human history is filled with stories of depravity. The Sawney Beane case in the early seventeenth century is one of most heinous examples, concerning a family that lived in a cave and chose murder, cannibalism, and incest as its way of life. For twenty-five years this family, rejecting all accepted standards of human behaviour and morality, carried on a vicious war against humanity. Even a medieval world accustomed to torture and violence was horrified. Because over the years a large family was ultimately involved, most of whom had been born and raised in fantastic conditions under which they accepted such an existence as normal, taking their standards from the criminal behaviour of their parents, the case raises some interesting legal and moral issues. Retribution when it finally came was quick and merciless, but for many of the forty-eight Beanes who were put to death it may have been unjust.

The case is simple enough, and has been well authenticated. Sawney Beane was a Scot, born within a few miles of Edinburgh in the reign of James VI of Scotland, who was also James I of England. His father worked the land, and Sawney was no doubt brought up to follow the same hard working, honorable career. But Sawney soon discovered that honest work of any kind was not his forte. At a very early age he began to exhibit what today would be regarded as delinquent traits. He was lazy, cunning and vicious, and resentful of authority of any kind.

As soon as he was old enough to look after himself he decided to leave home and live on his wits. They were to serve him well for many years. He took with him a young woman of an equally irresponsible and evil disposition, and they went to set up “home” together on the Scottish coast by Galloway.

Home turned out to be a cave in a cliff by the sea, with a strip of yellow sand as a forecourt when the tide was out. It was a gigantic cave, penetrating more than a mile into the solid rock, with many tortuous windings and side passages. A short way from the entrance of the cave all was complete darkness. Twice a day at high tide several hundred yards of the cave’s entrance passage were flooded, which formed a deterrent to intruders. In this dark damp hole they made their home. It seemed unlikely that they would ever be discovered. In practice, the cave proved to be a lair rather than a home, and from this lair Sawney Beane launched a reign of terror which was to last for a quarter of a century. It was Sawney’s plan to live on the proceeds of robbery, and it proved to be a simple enough matter to ambush travelers on the lonely narrow roads connecting nearby villages. In order to ensure that he could never be identified and tracked down, Sawney made a point of murdering his victims.

His principle requirement was money with which he could buy food at the village shops and markets, but he also stole jewelry, watches, clothing, and any other articles of practical or potential value. He was shrewd enough not to attempt to sell valuables which might be recognized; these were simply stock-piled in the cave as unrealizable assets.

Although the stock-pile grew, the money gained from robbery and murder was not sufficient to maintain even the Sawney Beanes modest standard of living. People in that wild part of Scotland were not in the habit of carrying a great deal of money on their persons. Sawney’s problem was how to obtain enough food when money was in short supply and any attempt to sell stolen valuables taken from the murdered victims might send him to the gallows. He chose the simple answer. Why waste the bodies of the people he had killed? Why not eat them?

This is what he and his wife proceeded to do. After an ambush on a nearby coastal road he dragged the body back to the cave. There, deep in the Scottish bedrock, in the pallid light of a tallow candle, he and his wife disemboweled and dismembered the victim. The limbs and edible flesh were dried, salted and pickled, and hung on improvised hooks around the walls of the cave to start a larder of human meat on which they were to survive, indeed thrive, for more than two decades. The bones were stacked in another part of the cave system.

Naturally, these abductions created intense alarm in the area. The succession of murders had been terrifying enough, but the complete disappearance of people traveling alone along the country roads was demoralizing. Although determined efforts were made to find the bodies of the victims and their killer, Sawney was never discovered. The cave was too deep and complex for facile exploration. Nobody suspected that the unseen marauder of Galloway could possibly live in a cave which twice a day was flooded with water. And nobody imagined for a moment that the missing people were, in fact, being eaten.

The Sawney way of life settled down into a pattern. His wife began to produce children, who were brought up in the cave. The family were by no means confined to the cave. Now that the food problem had been satisfactorily solved, the money stolen from victims could be used to buy other essentials. From time to time they were able to venture cautiously and discreetly into nearby towns and villages on shopping expeditions. At no time did they arouse suspicion. In themselves they were unremarkable people, as in the case with most murders, and they were never challenged or identified.

On the desolate foreshore in front of the cave the children of the Beane family no doubt saw the light of day, and played and exercised and built up their strength while father or mother kept a look-out for intruders—perhaps as potential fodder for the larder.

The killings and cannibalism became habit. It was survival, it was normal, it was a job. Under these incredible conditions Sawney and his wife produced a family of fourteen children, and as they grew up the children in turn, by incest, produced a second generation of eight grandsons and fourteen granddaughters.

It is astonishing that with so many children and, eventually, adolescents milling around in and close to the cave somebody did not observe this and investigate. The chances are that they did, from time to time—that they investigated too closely and were murdered and eaten. The Sawney children were no doubt brought up to regard other humans as food. The young Sawneys received no education, except in the arts of primitive speech, murder and cannibal cuisine. They developed as a self-contained expanding colony of beasts of prey, with their communal appetite growing ever bigger and more insatiable. As the children became adults they were encouraged to join in the kidnappings and killings. The Sawney gang swelled its ranks to a formidable size. Murder and abduction became refined by years of skill and experience to a science, if not an art.

Despite the alarming increase in the number of Sawney mouths which had to be fed, the family were seldom short of human flesh in the larder. Sometimes, having too much food in store, they were obliged to discard portions of it as putrefaction set in despite the salting and pickling. Thus it happened that from time to time at remote distances from the cave, in open country or washed up on the beach, curiously preserved but decaying human remains would be discovered. Since these grisly objects consisted of severed limbs and lumps of dried flesh, they were never identified, nor was it possible to estimate when death had taken place, but it soon became obvious to authority that they were connected with the long list of missing people. And authority, at first disbelieving, began to realize with gathering the nature of what was happening. Murder and dismemberment were one thing, but the salting and pickling of human flesh implied something far more sinister.

The efforts made to trace the missing persons and hunt down their killers resulted in some unfortunate arrests and executions of innocent people who se only crime was that they had been the last to see the victim before his, or her, disappearance. The Sawney family, secure in their cave, remained unsuspected and undiscovered.

Years went by. The family grew older and bigger and more hungry. The program of abduction and murder was organized on a more ambitious scale. Sometimes as many as six men and women would be ambushed and killed at a time by a dozen or more Sawney’s. Their bodies were always dragged back to the cave to be prepared by the women for the larder. It seems strange that nobody ever escaped to provide the slightest clue to identify the domicile of his attackers, but the Sawney’s conducted their ambushes like military operations, with “guards” concealed by the road at either side of the main center of attack to cut down any quarry tried to run for it. This “three-pronged” operation proved effective; there were no survivors. And although mass searches were carried out to locate the perpetrators of these massacres, nobody ever thought of searching the deep cave. It was passed by on many occasions.

Such a situation could not continue indefinitely, however. Inevitably there had to be a mistake, just one clumsy mistake that would deliver the Sawney Beane family to the wrath and vengeance of outraged society. The mistake, when it happened, was simple enough, the surprising thing was that it had not happened earlier. For the first time in 25 years the Sawneys, through bad judgment and bad timing, allowed themselves to be outnumbered, though even that was not the end of the matter. Retribution when it finally came was in the grand manner, with the King himself talking part in the pursuit and annihilation of the Sawney Beane tribe.

It happened this way. One night a pack of the Sawney Beanes attacked a man and his wife who were returning on horse-back from a nearby fair. They seized the woman first, and while they were still struggling to dismount the man had her stripped and disemboweled, ready to be dragged off to the cave. The husband, driven berserk by the swift atrocity and realizing that he was hopelessly outnumbered by utterly ruthless fiends, fought desperately to escape. In the vicious engagement some of the Sawney’s were trampled underfoot.

But he, too, would have been taken and murdered if a group of other riders, some twenty or more, also returning from the fair, hadn’t arrived unexpected on the scene. For the first time the Sawney Beanes found themselves at a disadvantage, and discovered that courage was not their most prominent virtue. After a brief violent skirmish they abandoned the fight and scurried like rats back to their cave, leaving the mutilated body of the woman behind, and a score of witnesses. This was to be the Sawney’s first and last serious error of tactics and policy.

The man, the only one on record known to have escaped from a Sawney ambush, was taken to the Chief Magistrate of Glasgow to describe his harrowing experience. This evidence was the break for which the magistrate had been waiting for a long time. The long list of missing people and pickled human remains seemed to be reaching its final page. A gang of men and youths were involved, and had been involved for years, and they had to be tracked down. They obviously lived locally, in the Galloway area, and past discoveries suggested that they were cannibals. The disemboweled woman proved the point.

The matter was so serious that the Chief Magistrate communicated directly with King James VI and the King apparently took an equally serious view, for when he went in person to Galloway with an army of four hundred armed men and a host of tracker dogs, the Sawney Beanes were in trouble.

The King, with his army, set out systematically on one of the biggest manhunts in history. They explored the entire Galloway countryside and coast, discovering nothing. When patrolling the shore they would have walked past the partly waterlogged cave itself had not the dogs, scenting the faint odor of death and decay, started baying and howling and trying to splash their way into the dark interior.

This seemed to be it. The pursuers took no chances. They knew they were dealing with vicious, ruthless men who had been in the murder business for a long time. With flaming torches to provide a flickering light, and swords at the ready, they advanced cautiously but methodically along the narrow twisting passages of the cave. In due course they reached the charnel house at the end of the mile-deep cave that was the home and operational base of the Sawney Beane cannibals.

A dreadful sight greeted their eyes. Along the damp walls of the cave human limbs and cuts of bodies, male and female, were hung in rows like carcasses of meat in a butchers cold room. Elsewhere they found bundles of clothing and piles of valuables, including watches, rings and jewelry. In an adjoining cavern there was a heap of bones collected over some twenty five years.

The entire Sawney Beane family, all forty-eight of them, were in residence, lying low, knowing that an army four hundred strong was on their tail. There was a fight, but for the Sawney’s there was literally no escape. The exit from the cave was blocked with armed men who meant business. They were trapped and duly arrested. With the King himself still in attendance they were marched to Edinburgh, but not for trial. Cannibals such as the Sawneys did not merit the civilized amenities of judge and jury. The prisoners numbered twenty seven men and twenty one women of which all but two, the original parents, had been conceived and brought up as cave-dwellers, raised from childhood on human flesh, and taught that robbery and murder were the normal way of life. For this wretched incestuous horde of Scottish cannibals there was to be no mercy, and no pretense of justice.

The Sawney Beanes of both sexes were condemned to death in an arbitrary fashion because their crimes over a generation of years were adjudged to be so infamous and offensive as to preclude the normal process of law, evidence and jurisdiction. They were outcasts of society and had no rights, even the youngest and most innocent of them.

All were executed the following day, in accordance with the conventions and procedures of the age. The men were dismembered, just as they had dismembered their victims. Their arms and legs were cut off while they were still alive and conscious, and they were left to bleed to death, watched by their women. And then the women were burned like witches in great fires.

At not time did any one of them express remorse or repentance. But, on the other hand, it must be remembered that the children and grandchildren of Sawney Beane and his wife had been brought up to accept the cave dwelling cannibalistic life as normal. They had known no other life, and in a very real sense they had been well and truly “brain-washed,” in modern terminology. They were isolated from society, and their moral and ethical standards were those of Sawney Beane himself. He was the father figure and mentor in a small tightly integrated community. They were trained to regard murder and cannibalism as right and normal, and they saw no wrong in it. It poses the question as to how much of morality is the product of the environment and training, and how much is, or should be, due to some instinctive but indefinable inner voice of, perhaps, conscience. Did the young members of the Beane clan know that what they were doing was wrong?

Whether they knew or not, they paid the supreme penalty just the same.

Stop Spreading Germs

Take a Nap For Better Physical and Emotional Health

For many of us, more hours of shut-eye at night just doesn’t seem to be in the cards. Is there anything we can do? Yes. Naps. Wonderful, glorious naps. They’re not a full-on substitute for lack of sleep but they can do much more than you think and in less time than you’d guess. Without them, you’re going to be a mess. Here’s why.

Lack of sleep not only makes you ugly and sick, it also makes you dumb: missing shut-eye makes sixth graders as smart as fourth graders.

And if that’s not enough, lack of sleep contributes to an early death.

Starting in the mid-1980s, researchers from University College London spent twenty years examining the relationship between sleep patterns and life expectancy in more than 10,000 British civil servants. The results, published in 2007, revealed that participants who obtained two hours less sleep a night than they required nearly doubled their risk of death.

Maybe you think you don’t need all that much sleep. You’re wrong.

Less than 3 percent of people are actually 100 percent on less than eight hours a night. But you feel fine, you say? That’s the fascinating thing about chronic sleep debt. Research shows you don’t notice it — even as you keep messing things up.

Now here’s the part you’ve probably never heard:

Eight hours might not even be enough. Give people 10 hours and they perform even better.

Timothy Roehrs and Thomas Roth at the Sleep Disorders Research Center of the Henry Ford Hospital in Detroit, Michigan, have demonstrated that alertness significantly increases when eight-hour sleepers who claim to be well rested get an additional two hours of sleep. Energy, vigilance, and the ability to effectively process information are all enhanced, as are critical thinking skills and creativity.

I know what you’re thinking: 10 hours a night? I don’t have time for that. I barely have time to read this post. Is there a compromise? Naps. Can closing your eyes for a few minutes really make that much of a difference? Keep reading.

Research shows naps increase performance. NASA found pilots who take a 25 minute nap are 35 percent more alert and twice as focused.

Research by NASA revealed that pilots who take a 25-minute nap in the cockpit — hopefully with a co-pilot taking over the controls — are subsequently 35 percent more alert, and twice as focused, than their non-napping colleagues.

Little siestas helped people across a whole host of measures. Improved reaction time, fewer errors…

NASA found that naps made you smarter — even in the absence of a good night’s sleep.

If you can’t get in a full night’s sleep, you can still improve the ability of your brain to synthesize new information by taking a nap. In a study funded by NASA, David Dinges, a professor at the University of Pennsylvania, and a team of researchers found that letting astronauts sleep for as little as 15 minutes markedly improved their cognitive performance, even when the nap didn’t lead to an increase in alertness or the ability to pay more attention to a boring task.

Researchers at the University of California, Berkeley, found that napping for ninety minutes improved memory scores by 10 percent, while skipping a nap made them decline by 10 percent.

Studies show we can process negative thoughts quite well when we’re exhausted — just not the happy ones.

Negative stimuli get processed by the amygdala; positive or neutral memories get processed by the hippocampus. Sleep deprivation hits the hippocampus harder than the amygdala. The result is that sleep-deprived people fail to recall pleasant memories, yet recall gloomy memories just fine.

What’s not to love? I know. You’re busy. You’ll just have another cup of coffee. Sorry, research shows naps beat caffeine.

So how do you nap the right way? How do you get the results you want with minimal effort? Here’s what science says.

Whatever your limitations and desires, there’s a nap for you. Looking at research from Richard Wiseman and the WSJ, here’s a breakdown.

Which one describes what you need?

1) “I just need to be more alert and focused”:

Take a 10-20 minute nap. You’ll get a boost in alertness and focus for two hours or more, pay off a little sleep debt, and even reduce blood pressure.

2) “Brain no working. Need smartz”:

Consider a 60 minute nap. You’ll get all the benefits of the 10-20 minute nap while also improving memory and learning.

But be warned: 60 minute naps cause grogginess.

3) “I want it all, baby”:

Take a 90 minute nap. This allows your brain to experience a complete sleep cycle.

You’ll get the full whack: increased alertness, memory, learning, creativity, and performance — with no post-nap grogginess.

4) “I don’t know what I want but you’ve scared me into napping and I don’t have much time”:

Go with 10 minutes. It beat five, 20, or 30 minute naps in a comparative research study.

5) “I don’t have enough time to tell you how little time I have”:

No nap is too short: “A 2008 study showed that even a nap of a few minutes provided benefits. Just anticipating a nap lowers blood pressure.”

When is the best time to nap? Salk Institute researcher Sara Mednick generally recommends you nap approximately six to seven hours after waking.

Trouble falling asleep? Write down any worries and think positive (but not exciting) thoughts. Trying too hard to sleep is counterproductive.

Worried you won’t wake up in time? Richard Wiseman recommends a cup of coffee immediately before napping. The caffeine will kick in 25 minutes after you lay down.

We’d all be better off with 10 hours of sleep a night — but that’s not going to happen for most of us.

Naps can boost performance and help make up for some of the problems sleep deprivation can cause.

Ted Nugent Self-Destructs

In a week when two casinos operated by different Native American tribes canceled three separate Nugent shows set for next month and dozens protested a concert in New Jersey, concert touring experts say the National Rifle Association board member and conservative commentator is doing real damage to his money-earning potential.

“If you’re going to say something political, you’re going to have some backlash, it doesn’t matter who you are or what you say,” said Larry Magid, a Philadelphia-based promoter who has handled Stevie Wonder, Fleetwood Mac, and Bette Midler. “Nugent seems to have taken it to extremes. I don’t know that you can blame anyone for not wanting to play him for all of the baggage that he brings.”

Magid, who also organized the famed 1985 Live Aid benefit show in Philadelphia, said Nugent was never a huge concert draw, but his declaration earlier this year that President Barack Obama is a “subhuman mongrel” may mark a turning point.

“I don’t know if that is frustration at not being a viable act, but it is stupid,” Magid said of Nugent. “If you are a musician, you are trying to bring your music, your art to a broad group of people. It is one thing to take a stance, it is another thing when you are talking about the president of the United States.

“For all of the people enamored with him, there are 20 or 30 or 40 times that who are not enamored with him. To me, it’s not bright. If I’m a promoter I have to think two or three or four times before I take a shot with this performer.”

“No one should be surprised by any of this,” said Gary Bongiovanni, editor-in-chief of Pollstar USA, which tracks concert touring receipts. “It’s a free country and Nugent has always had a big mouth. But if he keeps making incendiary statements his future tours may be limited to NRA conventions and Fox News events.”

Damn! That was both brutal and clearly extremely accurate.

Nugent was never that popular of a musician anyway, and now with his racism and misogyny on full display it is amazing that ANYBODY attends his concerts.

Well besides Right Wing nuts, paint chip eaters, and fellow pedophiles that is.

Most Expensive Meat

Jamón Ibérico de bellota refers to the cured leg of a pata negra pig that has been raised free-range in the old-growth oak forests of western Spain. The pigs eat a diet rich in acorns, wild mushrooms, herbs, and grasses, yielding meat that’s richly flavored and low in saturated fat. Each ham is cured for a minimum of two years before reaching the market.

A 15-pound bone-in leg of jamón Ibérico de bellota retails for around $1,300, or $87 per pound.

The acorn-rich forests of western Spain make up an ecosystem that exists nowhere else in the world, and each pig requires at least 2 acres of land for ample foraging. That, in turn, strictly limits the amount of jamón Ibérico de Bellota available each year.