Monthly Archives: April 2014

Fast Food Nation

Little-Known Punctuation Marks You Might Want to Use

Because sometimes periods, commas, colons, semi-colons, dashes, hyphens, apostrophes, question marks, exclamation points, quotation marks, brackets, parentheses, braces, and ellipses won’t do.

INTERROBANG

The interrobang is a combination exclamation point and question mark, and can be replaced by using one of each.

PERCONTATION POINT OR RHETORICAL QUESTION MARK

The backward question mark was proposed by Henry Denham in 1580 as an end to a rhetorical question, and was used until the early 1600s.

IRONY MARK

It looks a lot like the percontation point, but the irony mark’s location is a bit different, as it is smaller, elevated, and precedes a statement to indicate its intent before it is read. Alcanter de Brahm introduced the idea in the 19th century, and in 1966 French author Hervé Bazin proposed a similar glyph in his book, Plumons l’Oiseau, along with 5 other innovative marks.

LOVE POINT

Among Bazin’s proposed new punctuation was the love point, made of two question marks, one mirrored, that share a point. The intended use, of course, was to denote a statement of affection or love, as in “Happy anniversary [love point]” or “I have warm fuzzies [love point]

ACCLAMATION POINT

Bazin described this mark as “the stylistic representation of those two little flags that float above the tour bus when a president comes to town.” Acclamation is a “demonstration of goodwill or welcome,” so you could use it to say “I’m so happy to see you [acclamationpoint]” or “Viva Las Vegas [acclamationpoint]”

CERTITUDE POINT

Need to say something with unwavering conviction? End your declaration with the certitude point, another of Bazin’s designs.

DOUBT POINT

This is the opposite of the certitude point, and thus is used to end a sentence with a note of skepticism.

AUTHORITY POINT

Bazin’s authority point “shades your sentence” with a note of expertise, “like a parasol over a sultan.” Likewise, it’s also used to indicate an order or advice that should be taken seriously, as it comes from a voice of authority.

SARCMARK

The SarcMark (short for “sarcasm mark”) was invented, copyrighted and trademarked by Paul Sak, and while it hasn’t seen widespread use, Sak markets it as “The official, easy-to-use punctuation mark to emphasize a sarcastic phrase, sentence or message.” Because half the fun of sarcasm is pointing it out [SarcMark].

SNARK MARK

This, like the copyrighted SarcMark, is used to indicate that a sentence should be understood beyond the literal meaning. Unlike the SarcMark, this one is copyright free and easy to type: it’s just a period followed by a tilde.

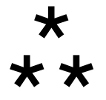

ASTERISM

This cool-looking but little-used piece of punctuation used to be the divider between subchapters in books or to indicate minor breaks in a long text. It’s almost obsolete, since books typically now use three asterisks in a row to break within chapters (***) or simply skip an extra line. It seems a shame to waste such a great little mark, though. Maybe we should bring this one back.

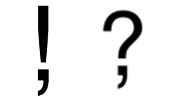

EXCLAMATION COMMA & QUESTION COMMA

Now you can be excited or inquisitive without having to end a sentence! A Canadian patent was filed for these in 1992, but it lapsed in 1995, so use them freely, but not too often.

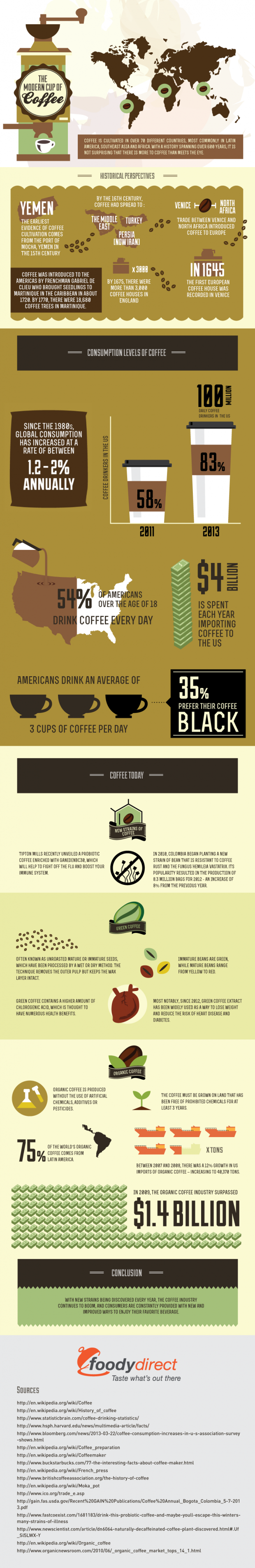

Picture Made of One Million Coffee Beans

Assume

Sourdough

Truths About Morgan Freeman

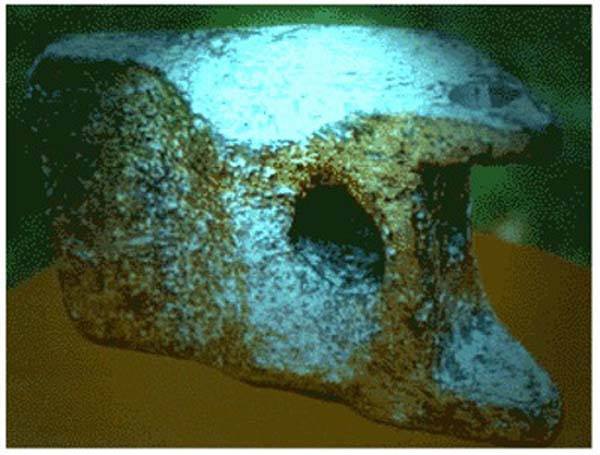

Aluminum Wedge of Aiud

There are enigmatic artifacts found worldwide that simply do not fit the accepted geologic or historical timeline. These ancient anomalies, also referred to as ooparts (out-of-place artifacts), are objects that by scientific measure are very old, but in form or construction appear to be quite modern. If our current history of the world is correct, they just should not exist. And there are many more examples than geologists, archaeologists, and other scientists care to admit. One example I recently found out about is the Aluminum Wedge of Aiud. This particular artifact is a true enigma.

In 1974, in Romania, East of Aiud, a group of workers, on the banks of the river Mures, discovered three buried objects in a sand trench thirty-five feet deep. Two of the objects proved to be Mastodon bones. These dating from between the Miocene and the Pleistocene periods.

The third object, the Aluminum Wedge of Aiud, also known as the Object of Aiud, is a mysterious wedge-shaped block of metal similar in some respects to the head of a hammer. The object was sent to the archeological institute of Cluj-Napoca. The examination of this object showed it to weigh about five pounds. There are two holes of different sizes. The object has two arms. Traces of tool marks can be seen on the sides of the object and at its lowest part. It measures approximately 8″ x 5″ x 3″.

Dr. Niederkorn of the institute for the study of metals and minerals located in Magurele, Romania, concluded that the object is comprised of a alloy of an extremely complex metal. Twelve different elements combine to form the Aiud Object. It consists of: 89% aluminum, 6.2% copper, 2.84% silicon, 1.81% zinc, 0.41% lead, 0.33% tin, 0.2% zirconium, 0.11% cadmium, 0.0024% nickel, 0.0023% cobalt, 0.0003% bismuth, and trace of galium.

Furthermore, this strange object is covered with a thick layer of aluminum oxide, which lends credence to its antiquity. After the analysis of this aluminum oxide layer, specialists have confirmed that the object is a minimum of 300 to 400 years old.

The fact that this strange metal object was found alongside Mastadon bones does cause one to wonder and raises many issues. These findings helped to ignite a heated debate within the scientific community.

The results puzzled the researchers because aluminum wasn’t discovered until 1808, and not produced commercially until 1885. Aluminum is not found freely in nature, but is found in combination with other minerals which must be separated from it. The manufacturing process required to achieve this process requires 1,000 degrees of heat.

Other specialists claim that the object could be 20,000 years old because it was found in a layer with mastodon bone. Perhaps this particular specimen lived in the latter part of the Pleistocene.

Some researchers suppose that this piece of metal was part of a flying object that had fallen into the river. They presume that it had an extraterrestrial origin. Other researchers believe the wedge was made here on Earth and its purpose and how it came to be made has not yet been identified.

Wisdom of Gandhi

When Mohandas Karamchand Ghandhi, better known as Ghandhi, was studying law at the University College of London, there was a professor, whose last name was Peters, who felt animosity for Gandhi, and because Gandhi never lowered his head towards him, their “arguments” were very common.

One day, Mr. Peters was having lunch at the dining room of the University and Gandhi came along with his tray and sat next to the professor. The professor, in his arrogance, said, “Mr Gandhi: you do not understand… a pig and a bird do not sit together to eat “.

Gandhi replied, “You do not worry professor, I’ll fly away “, and he went and sat at another table.

Mr. Peters, filled with rage, decided to take revenge on the next test, but Gandhi responded brilliantly to all questions. Then, Mr. Peters asked him, “Mr Gandhi, if you are walking down the street and find a package, and within it there is a bag of wisdom and another bag with a lot of money; which one will you take?”

Without hesitating, Gandhi responded, “the one with the money, of course”.

Mr. Peters, smiling, said, “I, in your place, would have taken the wisdom.

“Each one takes what one doesn’t have”, responded Gandhi indifferently.

Mr. Peters, already hysteric, wrote on the exam sheet the word “idiot” and gave it to Gandhi.

Gandhi took the exam sheet and sat down. A few minutes later, he went goes to the professor and said, “Mr. Peters, you signed the sheet, but you did not give me the grade.”

Things You Might Not Have Known Were Named After Real People

1. MESMERIZE

Franz Mesmer wasn’t a cheap vaudeville hypnotist. He was a doctor in the 18th century. And … he was sort of a quack. But just about everyone was a quack in those days; medical successes were measured by the least amount of people killed. So when Mesmer began to advocate a new healing technique he’d discovered, the use of what he called “animal magnetism,” people were open-minded. He believed that simply by sitting with a patient, looking in their eyes, and touching them in various medically appropriate places, he could cure them through natural magnetic force. The medical community didn’t buy it, but the public liked it. In the mid-1800s, long after Mesmer’s death, the term “mesmerize” had morphed into a synonym for hypnosis, and then later gained an even more fantastical definition, as “mesmerizing” became a popular stage act for magicians and vaudevillians.

2. DECIBEL

Alexander Graham Bell, man. He’s everywhere. Since he revolutionized how sound is transmitted and recorded, it seems fitting that his name should be used to help measure it. A “decibel” is one-tenth (deci) of a little-used unit of measurement called a “bel,” named, of course, after the Great One himself.

3. GALVANIZE

Luigi Galvani’s original work had nothing to do with covering metal with zinc to prevent rusting. It was actually much cooler. Galvani was an 18th century Italian scientist who electrocuted dead frogs to see their muscles twitch, which was pretty amazing at the time. So “to galvanize” originally meant to cause something to jolt into action, as if shocked by electricity. Then it meant shocked by electricity. Which is the base of electroplating, which is an earlier iteration of the chemical process we know as galvanization. See? It all checks out.

4. FUCHSIA

Leonhart Fuchs didn’t discover the fuchsia genus. He liked plants, though. He wrote a book called an herbal in 1542 about using plants as medication. His book was arguably the most highly regarded herbal of the Renaissance. So in the late 1600s, when French Botanist Charles Plumier discovered a new kind of flower in the Caribbean, he named it in honor of what must been have the botany version of Elvis, Fuchs. The subsequent color, which interestingly is interchangeable with the one called “magenta,” was coined in 1859.

5. MAVERICK

Other designers attacked his patents and, despite inventing an instrument that altered modern music as we know it, he was declared bankrupt twice before his death in 1894.

6. BAKELITE

If there is even a bit of antique-lover in you, you know how giddy the word “Bakelite” can make a collector feel. Bakelite was the first incarnation of synthetic plastic as we know it. It was heavy, rich-textured, held a vibrant color, and as a bonus, was non-flammable. It was a revolution in the 1920s, used for everything from jewelry to pipe stems. Though marketing couldn’t have come up with a more delicious name than “Bakelite” for its product, it was named for its inventor, Leo Baekeland. Baekeland was a brilliant chemist who patented more than 55 inventions and processes in his life. He died shortly after his son pressured him into retirement, after selling Bakelite to Union Carbide.

7. MACADAMIA NUTS

Macadamia nuts come from Australia, and the indigenous people there were eating them long before western botanists ever heard of them. They’re named for a famous 19th century chemist/politician John Macadam, but he didn’t discover them or introduce them to the west. His friend Ferdinand Von Mueller named them after him. That was after, as the story goes, Mueller sent the plant to be studied at the Botanical Gardens in Brisbane. The director told a student to crack open the new nut for germination. The student ate a few and said they were delicious. After waiting to see whether or not the young man would die in the following days, the director tasted a few himself and declared Macadamias the finest nut to have ever existed.

8. SHRAPNEL

Shrapnel, metal debris that flies at lethal speed from explosions, can be useful in warfare even when it’s not lethal. This is because shrapnel wounds more often than it kills, and it takes two solders to drag one wounded soldier off the battlefield. That might have been what Major General Henry Shrapnel had in mind when he began designing a new kind of bomb in 1784, what he called “spherical case” ammunition. It was a cannonball that contained lead shot, turning a cannon fire into an enormous shotgun blast. Forms of the shrapnel bomb (called an “anti-personnel” bomb) were used clear into WWI. The name eventually came to mean any fragmentation resulting from an explosion.

9. GRAHAM CRACKERS

Sylvester Graham, a 19th-century diet proponent, felt that people should ingest mostly fruits, vegetables, and whole grains while avoiding meats and any sort of spice. The upside of all of this bland food sounds a bit curious to the modern reader: Graham thought his diet would keep his patients from having impure thoughts. Cleaner thoughts would lead to less masturbation, which would in turn help stave off blindness, pulmonary problems, and a whole host of other potential pitfalls that stemmed from moral corruption. Graham invented the cracker that bears his name as one of the staples of this anti-self-abuse diet.

10. SALISBURY STEAK

James Salisbury was a 19th-century American doctor with a rather kooky set of beliefs. According to Salisbury, fruits, vegetables, and starches were the absolute worst thing a person could eat, as they would produce toxins as our bodies digested them. The solution? A diet heavy on lean meats. To help his diet cause, Salisbury invented the Salisbury steak, which he recommended patients eat three times a day and wash down with a glass of hot water to aid digestion. Apparently the only people paying attention to the doctor’s orders were elementary school lunch ladies.

11. NACHOS

Yep, there really was a guy named Nacho. In 1943 Ignacio Anaya—better known by his nickname “Nacho”—was working at the Victory Club in Piedras Negras, Mexico, just over the border from Eagle Pass, Texas. As the story goes, there were a lot of American servicemen stationed at Fort Duncan near Eagle Pass, and one evening a large group of soldiers’ wives came into Nacho’s restaurant as he was closing down.

Nacho didn’t want to turn the women away with empty stomachs, but he was too low on provisions to make a full dinner. So he improvised. Nacho Anaya supposedly cut up a bunch of tortillas, sprinkled them with cheddar and jalapenos and popped them in the oven. The women were so delighted with the nachos especiales that the snack quickly spread throughout Texas.